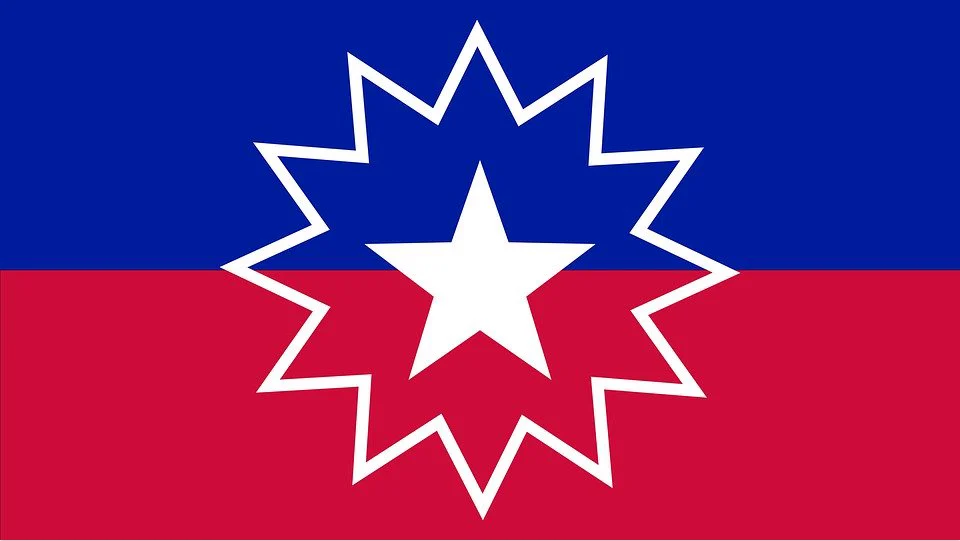

June 19 is Juneteenth. It’s a celebratory holiday I didn’t even know existed until I moved to Texas. It’s not an official national holiday, of course (or, not yet), but a celebration of the freeing of the last slaves in Galveston, Texas more than 2 years after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Here in Austin, it’s a day (or week) of celebrations, parades, live music, and black culture. Well, usually. It obviously looks a bit different this year. But it’s the perfect time to talk about the real problem of unequal access to the outdoors that exists for a whole race of people.

Because the truth is, while it’s easy to say that “nature doesn’t see color” (which, of course, strictly speaking, it doesn’t), the people in nature do. And people are the ones causing the problems. And it’s much harder to fix people. But the last few weeks we’ve spent lots of time diving into this issue and want to break down the misconceptions and issues we’ve learned about regarding unequal access to the outdoors, white people’s role in it, and what we can all do about it (even if we don’t think we’re the problem).

Unequal Access: Representation

Fo starters, many stories we’ve read or listed to about black outdoors people’s experience involve the simple fact that there is a serious lack of representation of black outdoor athletes in media and advertising. Go into an outdoor store and count how many posters or signs you see depicting a black individual. In most places they are few and far between. And if you look around places like that or log into Instagram or Facebook and all you see are white mountain bikers or skiers or backpackers, why would you want to jump in and join the fun? The narrative those ads and promos and magazines are showing is that there are white people outdoors. And if you don’t believe there’s no one in those spaces or sports who looks like you, why would you want to participate? It feels unwelcoming and exclusive, like a club you’re not allowed to be part of.

And while representation is certainly getting better, especially in light of current events, the photos are just the start.

Unequal Access: People are the Problem

Protests, murders, rallies, and raised voices the nation over have made one thing abundantly clear: racism still exists in our country. And that goes double in the outdoors where societal pressure and the watchful, judging eyes of others that occasionally keep people’s baser impulses in check in populated areas seem to disappear on the breeze. Current events also made one thing abundantly clear to us personally: we at Terradrift benefit immensely from white privilege. And we didn’t even realize it (that’s the foundation of white privilege). But it’s never too late to take action, stand up and say that black lives matter (in the outdoors and everywhere else), and take action to reduce the unequal access to the outdoors that plagues the black community.

I didn’t use to think unequal access existed. I honestly thought, but the great outdoors are open to all! But let’s back up a few years to the first time this phenomenon came to our attention. After backpacking in the Grand Canyon (national parks are prohibitively expensive for low-income individuals, BTW, making them decidedly not open to all), we emerged tired and sweaty and proud. We hopped on one of the free shuttles to go back to our car and at the next stop, a black couple hopped on. We very suddenly realized that those might have been the only black people we had seen in the 6 days we had been either on the rim or in the canyon. We couldn’t remember seeing a single other black individual.

People of color and diverse nationalities were everywhere: Latinos, Japanese and Chinese tourists, hikers from all over Europe, but no black individuals. This struck us a curious. And we wondered why that was the case. But that’s all we did was wonder. We didn’t research the issue or question any of our black friends or acquaintances. We didn’t do anything about it. But that, if nothing else, made our privilege as white people abundantly clear: not only did we not notice an entire group of people’s absence, we didn’t actually stop to figure out why they were absent to begin with and whether that was a problem.

White Privilege is Real (and Often Accidental)

But let’s go further back. We were both lucky to grow up in homes that were inclusive and taught us about the evils of racism. Homes that accepted everyone no matter their skin color. That said, we attended largely white schools and churches, which meant most of our friends were white. We didn’t even think about the ones that weren’t being black or brown; they were just our friends and we were just kids, totally out of touch with the dark side of the world.

Because of that, and our middle-class (if struggling middle class) upbringing, loving community, and sheltered young lives, racism was never something we actually witnessed. We knew it existed in the off-hand and largely oblivious remarks of older generations, and that always made us uncomfortable, but to think that people of color, blacks in particular, didn’t share the same access or enjoy the same activities as we did because of fear was totally unconscionable. They were just like us, weren’t they? Why would we have different access to different things?

Even as we became adults, we thought little of it and talked about it less. Probably because our friends and acquaintances of color just weren’t into the same things we were and we merely chalked it up to personal preference, never thinking that there may be larger considerations at play and that it could be because they didn’t want to go outdoors or didn’t feel safe outdoors. We never once thought that nature isn’t experienced equally among all people in all places (which is pretty much the definition of privilege).

That said, privilege was not a word we ever heard in the context of our skin color, though we suspected we were privileged in other ways: we had the opportunity to go to college (which we didn’t), attend a quality private school, and be taught about money and life skills and emotional and physical health by caring parents, all wonderful privileges. But here’s the thing: you usually don’t know you’re privileged until someone points it out to you. And then you kick and scream for a bit because, no you’re not!, but once you step back and take in the big picture, you can’t help but realize that, yeah, you really are. And you’re lucky for it.

But there’s a but…

Once you realize you have privilege, the right thing to do is to use it for good. At the very least, use it to better inform your actions and attitudes.

Privilege and Outdoor Access go Hand-in-Hand

As for the luck of privilege, when it comes to access to outdoor activities and sports, that luck doesn’t extend to everyone, even if they came from an upper- or middle-class neighborhood. And we (with much chagrin, I might add), didn’t realize this or start looking into why until recent events demanded our attention.

What we found was multi-faceted, but boils down to two main things: money and fear. Because the truth is, it costs money to play outside. Park entrance fees and campground reservations can be extremely expensive. Mountain bikes cost money. So do tents and backpacks and hydration reservoirs and ski lift tickets. But while lack of funds can affect people of any race, people of color, especially the black community, are often afraid to go into the woods because of what might happen to them when no one else is around and they find themselves face-to-face with not a natural predator like a bear or mountain lion, but a violent and racist human being.

We started reading stories from black outdoor enthusiasts and organizations. We heard of black fly fishermen’s tires being slashed. Of black women being glared at by white hikers. Of black climbers being told to leave politics out of it and just “shut up and climb.” Of black mountain bikers being laughed at. Of black outdoorsmen being told to stay out of “white” sports. Of black birders being unjustly accused of attacking white women. Of black campers being suspected of nefarious purposes while just looking for a campsite. Of young men being murdered on their daily run.

These stories brought tears to our eyes because we couldn’t imagine anyone doing these things to others because of the color of their skin. But they do. Even if it’s not physical violence, there’s emotional violence, threats, and the way people make other people who don’t look like them uncomfortable in outdoor spaces with looks and jokes and oppressive blanket statements about their place in the world. And all of a sudden it made a lot more sense why the black community doesn’t seek solace in the outdoors to the same degree that other races do: they don’t feel welcome. Because racism may run more rampant outdoors than in the city. And that’s a hard pill to swallow. And our hearts break every time we think of it.

Why Unequal Access to the Outdoors Matters

But why does any of this matter (other than being heart-wrenchingly unfair)? Because the outdoors shouldn’t just provide peace and escape and solace and healing and thrills and exhilaration and adventure and wonder for one group of people. Everyone should be able to head outdoors and experience the power of nature therapy, to feel restored after sleeping under the stars, to feel the stoke and the adrenaline rush that comes from summiting a peak or sending a route. These are not experiences that belong to one or two groups of people. It’s nature, and it should be–and should feel–like home to everyone. No fear, no racism, no hurt. Period. The outdoors does not belong to whites (remember, it all once belonged to this land’s indigenous populations).

What Can We Do?

But if we aren’t personally the ones making people of color, black individuals in particular, feeling unsafe in the places we go to find solace or adventure or escape, what on earth can we do? Fortunately, there’s been a lot of discussion on this subject recently, and the cries for help demand that we as white allies start by speaking out.

About what privilege is, for starters. Because the problem with white privilege (which isn’t a problem in and of itself, of course, but can be a problem depending on what you do with it), is that you often don’t even realize it exists. Hence this post. Since we’ve been shown what it looks like and the damage and obliviousness it causes, it’s now our responsibility to show others and open a dialogue. And then it’s your responsibility to keep it going.

Know that privilege exists, then do something about it. Don’t assume everyone feels the same in the outdoors as you. Make sure to offer a smile and make people of color feel welcome in the outdoors. Don’t brush off important conversations. Let your black friends and acquaintances be heard. Stand up for them if you hear other climbers/boarders/hikers/whoever throwing around off-hand (or blatant) comments about race. Read stories by black outdoors people. Follow them on Instagram to enlighten yourself and answer calls to action. Donate to or volunteer for organizations that help black youth (or adults) get outside and diversify the outdoors. Don’t be that person who comments on posts with phrases like, “but nature doesn’t see color!”

Be an ally. A friend. Someone who sees the truth, is willing to speak up, and isn’t afraid to act. Be someone who is open to real conversations with people who don’t look like you. And be welcoming. Because the outdoors absolutely should be accessible to all. Wander on.

We’re also donating the proceeds from all Terradrift clothing and gear sales to Black Outside, Inc. for the rest of June.